November 14, 2025: The International Federation of Landscape Architects – Asia Pacific Region (IFLA–APR) Congress opened in Mumbai on Friday with an urgent call to rethink how India’s major urban centres are growing. While cities like Mumbai, Thane, Navi Mumbai, and Pune continue to expand at unprecedented speed, experts at the event warned that ecological systems are not keeping pace with development.

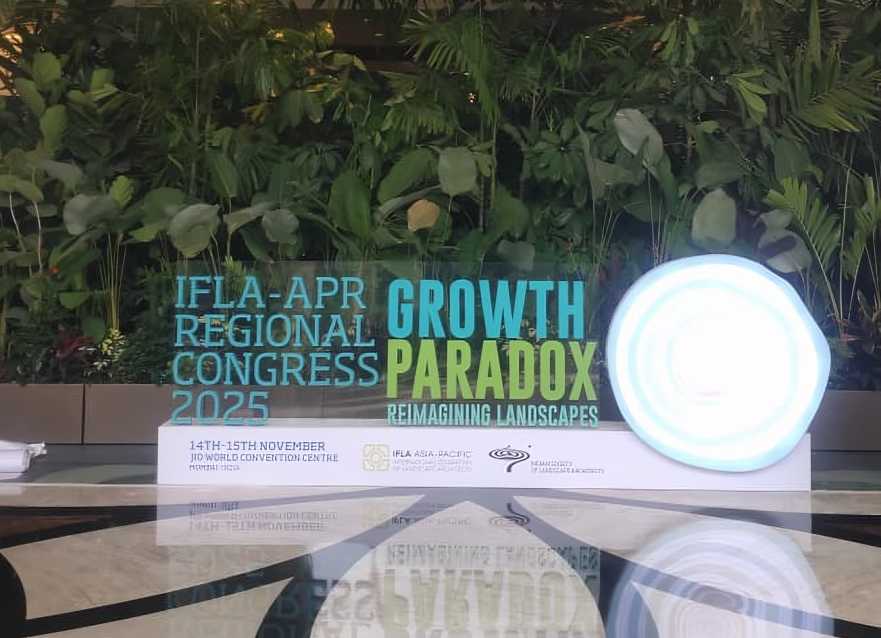

Hosted by the Indian Society of Landscape Architects (ISOLA) at the Jio World Convention Centre, the Congress, centred on the theme “Growth Paradox: Reimagining Landscapes,” brought global and Indian practitioners together to spotlight the widening ecological gaps in high-growth metropolitan regions.

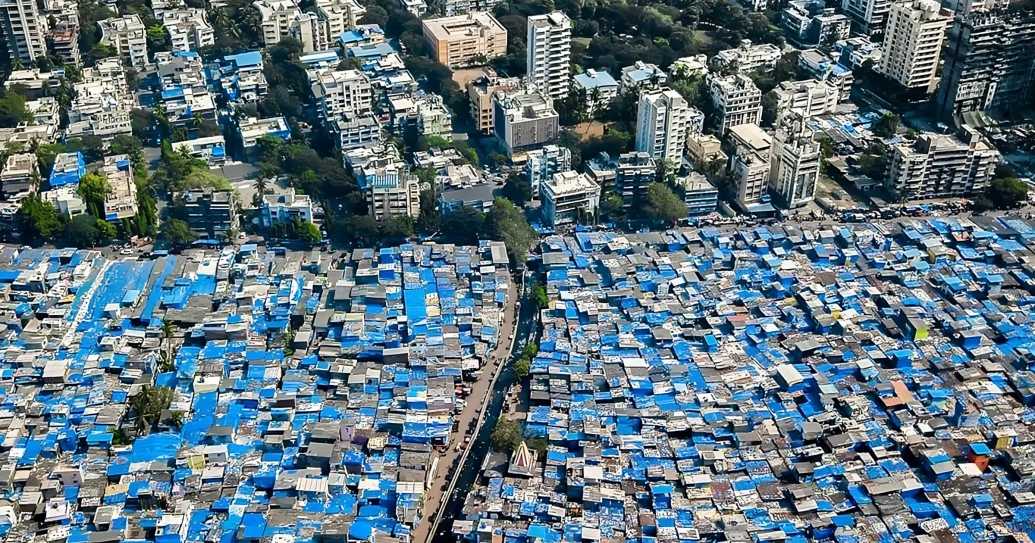

The core concern, speakers said, is not urban expansion itself but the fragmented, infrastructure-heavy pattern through which it unfolds. Rapid densification, shrinking open spaces, and stressed natural drainage pathways are now converging to increase heat vulnerability, disrupt water cycles, and heighten flood risk across Indian cities.

Industry expert Rakesh Parmar noted that the problem lies in growth occurring “without synchronising built development with the ecological systems that support it.” Real-estate markets, he added, are beginning to realise that long-term asset stability depends on landscape continuity and climate-sensitive planning—not just on maximising buildable land.

Much of the discussion centered on the development trajectory of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), which continues to densify along transport corridors, reclaimed coastlines, and peri-urban belts. Participants linked these trends to national LULC (land-use land-cover) patterns, showing how linear infrastructure, piecemeal zoning, and reclamation repeatedly sever ecological flows crucial for groundwater recharge, drainage, and heat mitigation.

Dr. Anju John, Architect, pointed out that planning decisions often precede complete ecological assessments. “Urban expansion in the MMR has advanced faster than the environmental data needed to guide it,” she said. “Development is inevitable, but without ecological intelligence built into planning frameworks, cities risk amplifying their own vulnerabilities.”

Academic presentations throughout the day reinforced this message. A study of the Chaliyar River Basin in Kerala revealed a three-decade decline in forests, waterbodies, and agricultural land, a pattern that researchers said mirrors emerging pressures in Mumbai’s fringes. Another study highlighted 31 abandoned quarries in Pune that remain unaccounted for in formal planning, despite their potential to function as micro-watersheds or community open spaces.

Ar. Shivali Lalbige emphasised the need to integrate such overlooked landscapes into metropolitan planning. “Cities expand into every available parcel, but seldom evaluate which lands should perform ecological functions rather than commercial ones,” she said. “A landscape-first approach can stabilise microclimates and reduce risks for surrounding developments.”

The Congress will continue through the weekend with sessions on coastal systems, resilient infrastructure, urban forests, and policy pathways for safeguarding ecological resilience in high-growth regions.